A special contribution from our team member, Kristen J. Schmidt, MSW, Ph.D.

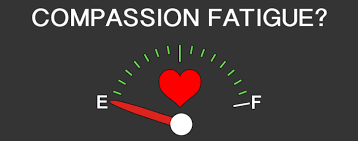

I began my clinical professional career over 30 years ago. As I reflect back, I am struck by the growth within the mental health profession. I have witnessed the development of evidence- based practices, trauma informed practices and a growth of knowledge about the issues practitioners can face when caring for individuals who experienced trauma. It now has a name: compassion fatigue.

Compassion Fatigue

Early in my career, I knew many therapists who quit. Some moved to other clinical environments, but many of them went into other professions altogether. We used the term “burnt out” but lacked a full understanding of why, how and what the best way is to respond. We supported mental health professionals with supervision, time off and the promotion of self-care.

Today we know so much more and can offer a comprehensive approach to address the two main components of compassion fatigue: burnout and vicarious trauma. Burnout can manifest itself with feelings of exhaustion, frustration and even depression. Symptoms of distress from vicarious trauma can include fear, anxiety, sleep disturbances and intrusive traumatic thoughts.

Many of us entered the profession because we wanted to help others. We tend to be compassionate, empathetic people. Combine this with the level of client/consumer severity, the workload, our own vulnerabilities and sometimes the extreme situations in which we work, it is easy to see how professionals can be at risk for compassion fatigue.

Prevention and Recovery

We know that prevention and/or recovery from compassion fatigue can be facilitated by awareness and anticipation of risk factors. The earlier we become aware of this issue ,the more likely practitioners can address those factors and even become resilient. Self-assessment tools are available to help identify our own personal factors.

When working in the field of trauma, it is imperative that we stay current in our professional knowledge and skill set. This includes utilizing supervision to address theory and practice, relationships, safety and vicarious trauma. Creating a peer support network, developing self-care measures and seeking personal clinical and medical therapy, when indicated, are also critical.

Importance of a Healthy Life Balance

I have personally tried to achieve a healthy balance in my life and realize that I came upon some helpful lifestyle activities quite by accident. Leaving work at work is easier said then done. Being a working mother, it didn’t seem possible to go for a walk, or engage in an activity like reading or gardening when I got home.

Yet, I somehow knew that a transition from work to home was indicated. For me it became cooking. And I found a way to engage my family in the process. I also changed my clothes as soon as I got home signaling to me and to others that my workday ended, and the family became my main focus. Later I found yoga, meditation and mindfulness to aid in creating a healthy work-life balance. Building in recreational activities, attending to hobbies and maintaining positive support systems also helped.

Trauma professionals often have a difficult time making their own needs a priority. What we have come to realize that by not doing so we are creating a liability for ourselves, the agencies we work for and those we are committed to serve.

Kristen J. Schmidt, MSW, Ph.D.

Accreditation Consultant for Accreditation Guru, Inc.